Credits. Nick Dines (02/06/2023)

Sfax and the sea

One of the things that strikes a first-time visitor to Sfax – Tunisia’s second city and important port and industrial centre – is that the sea is nowhere to be seen. There is no corniche like in Beirut, Alexandria or nearby Sousse. There is no immediate indication of beach or marine tourism. When you are in its vicinity, the sea’s absence is compensated by a set of tell-tale signs – the girders of cranes, rusting conveyor belts, stacks of containers, and the hulls of bulk carriers – which loom above a two-metre-high perimeter fence that blocks access to the port (Fig. 1).

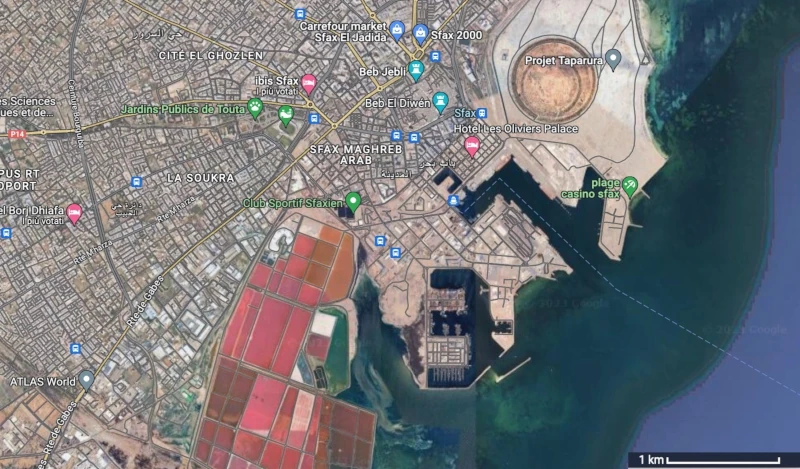

Looking at a map of Sfax, one is drawn to an odd-looking circular formation in a vast empty space directly north of the port (Fig. 2). This is the Taparura Project, a redevelopment scheme launched in the 1990s with the ultimate goal of transforming reclaimed land into a waterside district for 50,000 new residents (Barthel & Vignal, 2014). Construction, however, has yet to begin and, for the time being, the entire area remains off limits. To the south of the port lie the crimson-coloured Thyna Salinas, an enormous system of salt beds. If we discount the scruffy Casino Beach used by locals near the mouth of the harbour, all this means that Sfax is cut off from roughly ten kilometres of coastline. It is no wonder, then, that the sea itself is out of sight.

(Google Earth, 2023)

On our third morning in Sfax as part of the Vilmouv research project, we set off from the hotel outside the Medina in the direction of the sea. Our walk took us down pavement-less streets, alongside dusty palm trees and open railway tracks, past the inner habour and in between trucks belching diesel fumes (Fig. 3). We got as far as the ferry terminal for the Kerkennah Islands. Inside the terminal building and by the ferry ramp were members of the Tunisian National Guard checking the documents of passengers. Given that the Kerkennah Islands lay some forty kilometres closer to European territory, travel to them was now being controlled by the Tunisian state. Anyone without residence on the islands or in possession of a Schengen visa could be prevented from boarding. The premise was that a person with a Schengen visa had no interest in using the islands as a base for onward migration.

Credits. Nick Dines (31/05/2023)

Beyond the ferry terminal, the port continued to sprawl for at least another kilometre. It was possible to make out in the distance the dock where the Tunisian Coast Guard brought back migrants intercepted at sea. Later in the day, through a contact, one of the authors met with Maurice1 a West African who, thanks to his seafarer’s service book, had found work in the port; first on a fishing trawler and later in a boatyard. Every other morning, he would watch and count the figures who were brought ashore. That same morning, thirty or so migrants had disembarked from the Coast Guard’s ship.

It was not until two days later that we finally got a view of the open sea from the top-floor bar of the swanky but near empty Hotel Les Oliviers Palace.

If the sea’s location seemed somewhat elusive in Sfax, it was nevertheless continually invoked by the presence of foreign Black Africans on the city’s streets. Most but not all of these people – locally referred to with the racialized label ‘subsaharien’ – were here to cross the sea. In 2023, thousands had managed to traverse the Mediterranean, while hundreds had died along the Tunisian coast attempting to do so – 373 in April alone, the month before our visit to Sfax – and many were dying only a few kilometres from the city centre (FTDES 2023).

In fact, 2023 was the year that propelled Sfax to the centre of Western media attention. Reports in Europe’s leading dailies introduced readers to the quirkily-named southern Mediterranean city. It was from here that sub-Saharan African migrants were now understood to be setting off in flimsy metal boats: ‘In Sfax, Tunisia, sub-Saharan migrants dream of Europe’ (Masseguin 2023); ‘The boat had left Sfax, south of Tunis, a few days earlier (Tondo 2023); ‘One hundred and eighty kilometres separate Lampedusa from Sfax, Tunisia’s second city (Bonini et al. 2023); ‘The port city of Sfax shows us the great distance between desire and reality’ (Keilberth 2023).

Journalists all tended to converge around the idea of Sfax as a new urban node on the Central Mediterranean Route. Both the media interest and the crossings themselves had intensified following Kaïs Saied’s speech on 21 February 2023 during which the Tunisian president railed against a sub-Saharan African invasion and the threat of ethnic replacement. One month before, the Italian foreign and interior ministers had visited Tunisia to discuss the North African country’s collaboration in stopping Mediterranean crossings in exchange for the possibility of preferential entry quotas for Tunisian nationals.

As a direct consequence of the president’s speech, Maurice lost his job on the fishing trawler. Returning to Sfax after six days at sea, his boss had told him that Black Africans were being attacked on the streets and that he should lie low for a while. In any case, given the tense situation he could no longer employ him, although he recommended him to a friend’s boatyard for one tenth of his previous pay. Earning what he described as ‘peanuts’, Maurice’s goal was now to leave, and he had seafaring skills that could be put to use.

Inside Sfax: lying low and waiting

It was in the aftermath of Saied’s public endorsement of a European right-wing conspiracy theory and of the increase in deaths along the Tunisian shoreline that we travelled to Sfax. The city appeared to be in a lull. At the beginning of our stay, the police had evicted migrant traders from their pitches outside the Medina, only for many to return by the middle of the week. Meanwhile, everyday local Tunisians were queueing for hours to buy basic foodstuffs such as coffee. The sub-Saharan Africans we encountered, like Maurice, spoke of a growing sense of insecurity in Sfax after the President’s speech, but they also recounted their journeys through Mali and Algeria to get to Tunisia, and hinted at their preparations for departure.

Despite Western journalists suggesting the contrary, prospective sea-crossers do not actually leave from Sfax itself, but from a sixty-kilometre stretch of sandy shoreline to the north of the city. Sfax is the base camp for single or multiple attempts. The sub-Saharan Africans embody the city’s missing link with the sea, sometimes literally. An Italian researcher met during our visit recounted the story of a group of migrants intercepted at sea by the Tunisian Coast Guard, who were brought ashore several kilometres to the north of Sfax and left to walk back into the city in their sodden clothes.

Credits. Nick Dines (02/06/2023)

The nerve centre of ‘Base Camp Sfax’ is Rond-Point Beb Jebli, a major intersection situated to the immediate north of the Medina. Here vehicles compete for road space with jaywalking pedestrians. Opposite the entrance to the Medina sits Sfax 2000, a modern multi-storied clothes market, as well as the departure point for the main north-bound coastal routes. To the right is a busy suburban taxi rank and a concrete-clad park that has become home to recently arrived Sudanese and migrants who have been intercepted at sea. To the left are some parched patches of greenery surrounded by the 1990s high rise developments of El Jadida (Fig.4).

For sub-Saharan Africans, Beb Jebli roundabout plays multiple functions: a meeting point, a site of informal commercial transactions, a face-to-face forum for exchanging information, a transport hub and, for some, a precarious domicile. The roundabout also represents a sort of omphalos during their stay in Sfax. It is from here, adapting local methods of mapping the city, that people measure the distance to their places of abode and to the various points of embarkation. Hence north-east from Beb Jebli at Ave. Habib Bouguatfa Km 3.5 is Haffara, one of the city’s low-income districts that provides substandard accommodation to those waiting to leave (Fig. 5). At Km 18 one person had attempted their first crossing, while at Km 40 someone else had been off-loaded onto the beach by the Tunisian Coast Guard.

Credits. Nick Dines (02/06/2023)

Roundabout encounters

The concrete-clad park off Beb Jebli, officially known as Jardin de la Mère et de l’Enfant, is somewhat dilapidated and not particularly inviting. Over the railings that flank the central passageway are wet clothes hung out to dry. As we walk under a bridge that links two elevated sections of the park, a man in his early twenties calls down in English: ‘Where are you from?’ Hearing our reply and his question reciprocated, the man clambers down from the bridge to join us. We all shake hands. His tells us his name is Omar and that he comes from Sudan. He has been living in the park for some time with his companions who are laying on the grass behind the railings. A few days ago, he had set out to sea but was stopped by the Coast Guard and was now back in the park. He was not going to give up trying. ‘You’re from England? I’m a footballer and I want to play in the Premier League, but my dream is to play for Real Madrid. Do you have Instagram? Snapchat? Facebook?’ After a quick-fire round of questions and answers, Omar wandered back towards his companions with the parting words: ‘We’ll meet in Italy.’

By the entrance to the Medina, we meet Claire. Her migratory project is not oriented towards the sea. Rather, it has been slowly built around the roundabout since she moved to Sfax five years ago. Shortly after arrival, she discovered that she was pregnant but she has never stopped working. As she talks, she adroitly braids the hair of a woman perched on a stool. Behind her client sit other women who await their turn. As she works, Claire keeps an eye on her sprightly four-and-a-half-year-old daughter, Annette, to make sure she does not stray too far. She tells us that she regularly travels to the Côte d’Ivoire to visit her family. Europe does not interest her, she says. Aware of the increasing violence against sub-Saharan Africans, she just hopes the situation will not get worse. If this were to happen, she may decide to return home for good.

Credits. Nick Dines (02/06/2023)

It is from Beb Jebli that we set off to visit a group of 15 young Guinean men who share a three-bedroom ground-floor apartment in Haffara which they rent from a Tunisian family for 900 dinars (about 270 euros) a month. The day before we had spent time with three of the group in the centre of Sfax, including the brother of a 19-year-old whom one of the authors in Casablanca had met the previous week. During our visit to their home, two men dressed in gleaming robes return home from the mosque, the one safe space where they feel a bit more equal to local inhabitants, while another changes into sports gear and goes to Haffara Terrain, a nearby football pitch where different migrant communities from Guinea, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria organize games together.

With no chance of work, the men rely on money sent from relatives in Guinea. A boat crossing can cost between 1,500 and 5,000 dinars, although it is best to spend at least 3,000 dinars because anything less means travelling on badly-built, overcrowded boats and seriously risking your life. Tunisia is considered more convenient than Libya because you can pay in local currency rather than in dollars or euros. Most have been in Sfax for between 1 and 2 years and a few had spent up to 6 months working in Algiers. The latest addition to the household has just arrived from Algeria wearing the same plastic slip-ons that he used in the desert. Some of the men have already attempted to traverse the Mediterranean. One pulls a phone from his pocket, and unprompted plays us a video of himself and a female companion hiding under an olive grove near the coastal road where they were encamped for two days prior to boarding a boat. The mood of the video is quite jovial: we see them laughing, singing and conversing with friends on the phone. Another shows us photographs of himself in the desert in Algeria at night, waiting to cross the border. Mobile phones and social media represent important instruments of documentation and resistance, testified by the various Sfax-based Facebook accounts that post regular weather updates, name and shame swindlers encountered on route, mourn the deaths of brothers and sisters at sea and celebrate the safe arrival at destination of others.

Following the rise in attacks on Black Africans, the Guineans tended to move around Sfax in groups of at least three. On our return to the main road, we are shown the spot where a Beninois man was attacked and killed by a gang of Tunisian youths ten days earlier. We catch a taxi back into the centre. Two of the group – the taciturn brother of the contact in Casablanca and his more loquacious, English-speaking friend – hitch a ride with us and alight at Beb Jebli in front of the Medina.

After departure

Little over a month after our visit, Sfax was once again in the international news. On 4 July anti-migrant violence erupted in Sfax after a Tunisian man was stabbed to death by a Black African during a brawl. The death led to numerous evictions of Black Africans in Sfax and to many being rounded up by the police and dumped at the borders with Libya and Algeria. During the ensuing period, Rond-Point Beb Jebli became a refuge for hundreds of homeless migrants. On 17 July, following frequent visits by European leaders, a new agreement was signed between the EU and Tunisia whereby the latter agreed to cooperate more effectively on migration in exchange for considerable financial assistance to improve its border management. In the meantime, Maurice, the West African mariner, managed to reach Lampedusa and is now in southern France.

References

- Barthel, Pierre-Arnaud & Vignal, Leïla. (2014). ‘Arab Mediterranean Megaprojects after the ‘Spring’: Business as Usual or a New Beginning?’ Built Environment, 40(1), 52–71.

- Bonini, Carlo, Candito, Alessia & Martinelli, Leonardo. (2023). ‘I non grati.’ La Repubblica, 20 August.

- FTDES (Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Economiques et Sociaux). (2023). ‘Statistiques migration 2023’, 5 September.

- Keilberth, Mirco. (2023). ‘Als der Mob die Migranten aus ihren Wohnungen zerrte.’ Süddeutsche Zeitung, 20 July.

- Masseguin, Léa. (2023). « La vie est devenue très dure ici, tout le monde veut partir”: à Sfax, en Tunisie, les migrants subsahariens rêvent d’Europe.’ Libération, 1 August.

- Tondo, Lorenzo. (2023). ‘Baby among nine dead from cold and thirst on boat in Mediterranean.’ The Guardian, 3 February.

AUTEURS

DATE

Novembre 2023

CATÉGORIE

Sfax

CITER LA NOTICE